International real estate

International real estate qualifying for 2nd passport and residency

Citizenship by investment

Discover the Benefits of Citizenship Investment with Astons

Travel worldwide for business or pleasure without restrictions, including EU and UK

Residency by Investment

Unique opportunity to obtain visa free travel within the EU and UK and expand your business opportunities

Answers to frequently asked questions

While it depends a little on which residency or citizenship by investment scheme you apply to, most programmes offer whole family eligibility, with each individual granted a second passport or residency status. The age of the dependents varies from program to program – please check this with one of our consultants. That includes options to add a spouse or civil partner, dependent children, parents, sometimes siblings and grandparents to your application.

Astons has years of expertise expediting immigration by investment applications, with some of the opportunities allowing you to acquire a second passport in as little as 30 days! Other programmes require around three to four months. Some have phased citizenship with an initial residency period – although several investment schemes have the option of securing fast track processing for a nominal charge if you would like to relocate or secure a second passport faster.

Citizenship by investment offers an exceptional way to invest in emerging economies, sought-after property markets and businesses. Most second passport schemes require you to retain your investment for a minimum period, usually up to five years. However, when that period has passed, you can sell your investment to recoup the capital, often making a sizable profit in addition to returns earned in the meantime. If you opt for a non-refundable government donation route, then the value is not recoverable.

Once you have a second passport, you don’t need to do anything further to retain your citizenship other than comply with any requirements to maintain your investment for a certain number of years. When your passport falls due for renewal, you can request a replacement through the regular passport processing system in that country. Alternatively, please contact Astons if you need any assistance finding the quickest way to renew a second passport when the original expiry date is approaching.

A second passport is valid for life – you remain a citizen of that country indefinitely, with most citizenships passing down to your descendants. The only reason a passport might be revoked is if you breached a fundamental term of citizenship or residency program (such as selling your investments earlier than required by the program) or committed a serious offence in the country that issued the document.

Every country with a residency by investment or second citizenship scheme has benefits and incentives on offer. The differences include:

• Types of investment – ranging from property purchases to charitable donations.

• Invest thresholds – starting at $100,000 for Caribbean second passport schemes.

• Terms – you might not need to retain an investment or may need to keep a real estate acquisition for between three and five years.

• Travel rights – our supported programmes offer generous visa-free travel, including to prestigious destinations throughout Asia, Europe and the United States.

The Astons website includes detailed information for you to compare different immigration programmes, or our friendly team is always available to offer advice.

Alexander Kosovskiy

Investment Citizenship Expert

Any other questions?

Ask them to our analyst right now

Global Residence & Citizenship Solutions

Astons is an investment immigration firm offering residence and citizenship solutions in the EU & Caribbean.

Astons has over 30 years’ experience in providing holistic management of legal affairs for private clients, providing advice in investor immigration solutions, tax advisory, private education, asset structuring and investment services. Astons acts as Trusted Advisors to HNWIs and their families, as well as to leading lawyers, family offices, banks and investment firms around the world.

Our wealth of experience and highly-skilled multilingual immigration team and citizenship & residence advisors, ensures a truly international and personalised service, conducted with absolute discretion, speed and integrity. A firm with robust international connections, Astons has offices worldwide, including in UAE, USA, Malta, Cyprus, Turkey and Portugal.

Why Our Clients Choose Us

33 years of industry leadership and dominance - ASTONS is one of the original firms that molded the investment immigration industry. Founded in London in 1989, Astons has evolved into a family of global companies now headquartered in Dubai.

Astons personally serves clients via our global footprint with offices in Istanbul (Turkey), Limassol (Cyprus), Dubai (UAE),Athens (Greece), Fort Lauderdale (USA) and Saint Julians (Malta). As well as, via text message, WhatsApp, Telegram, or email.

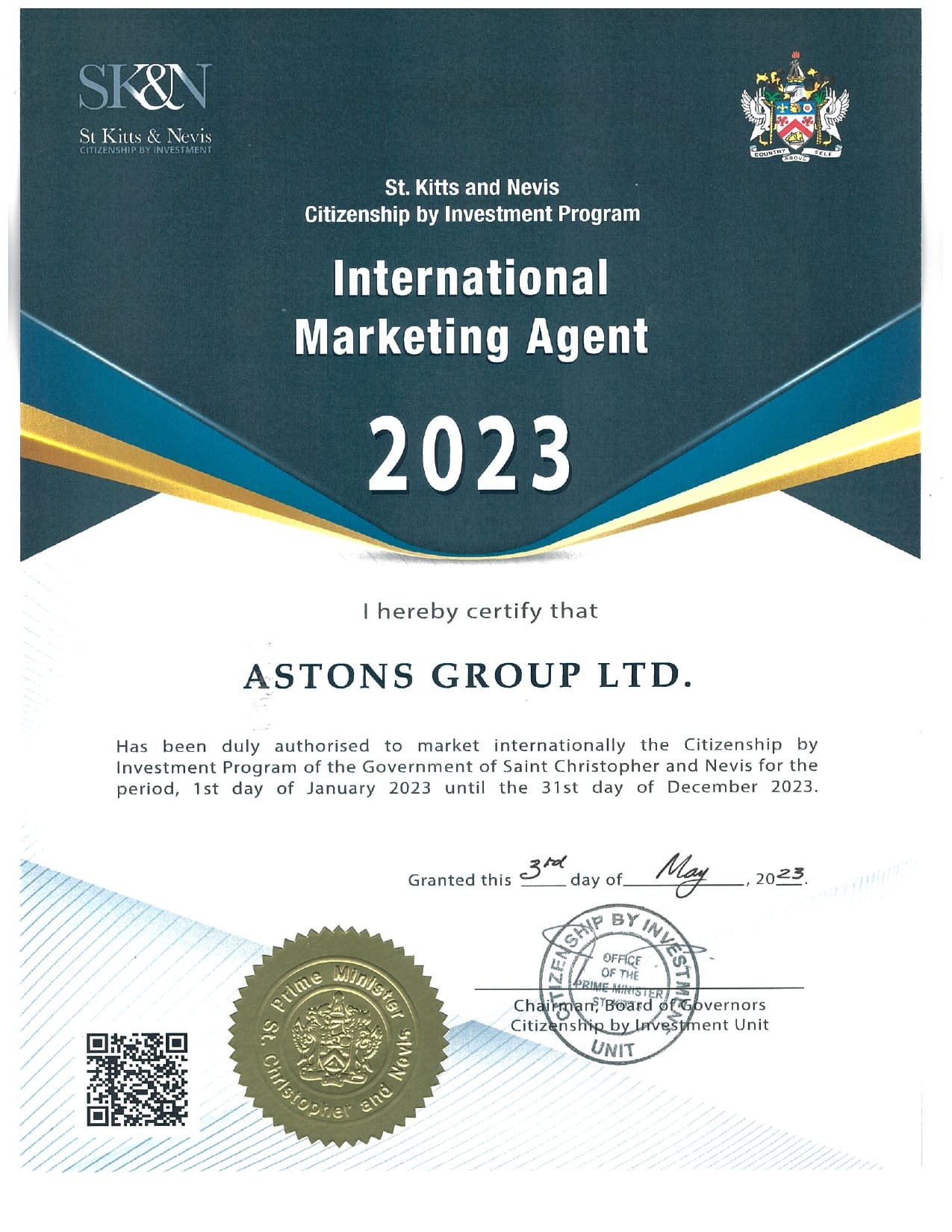

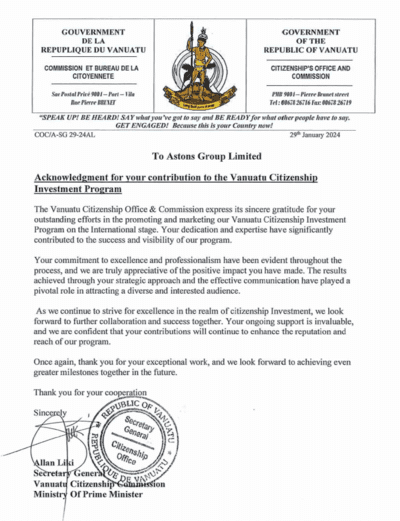

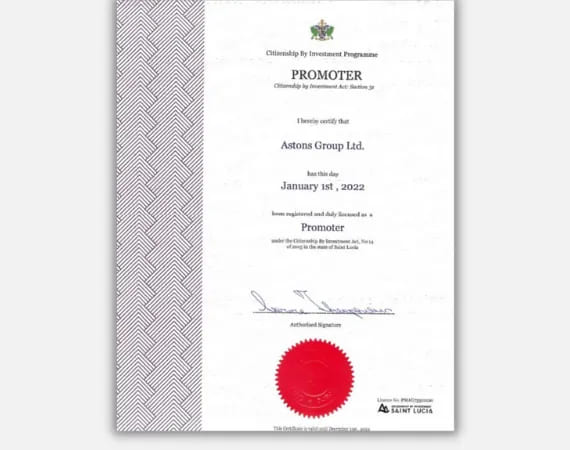

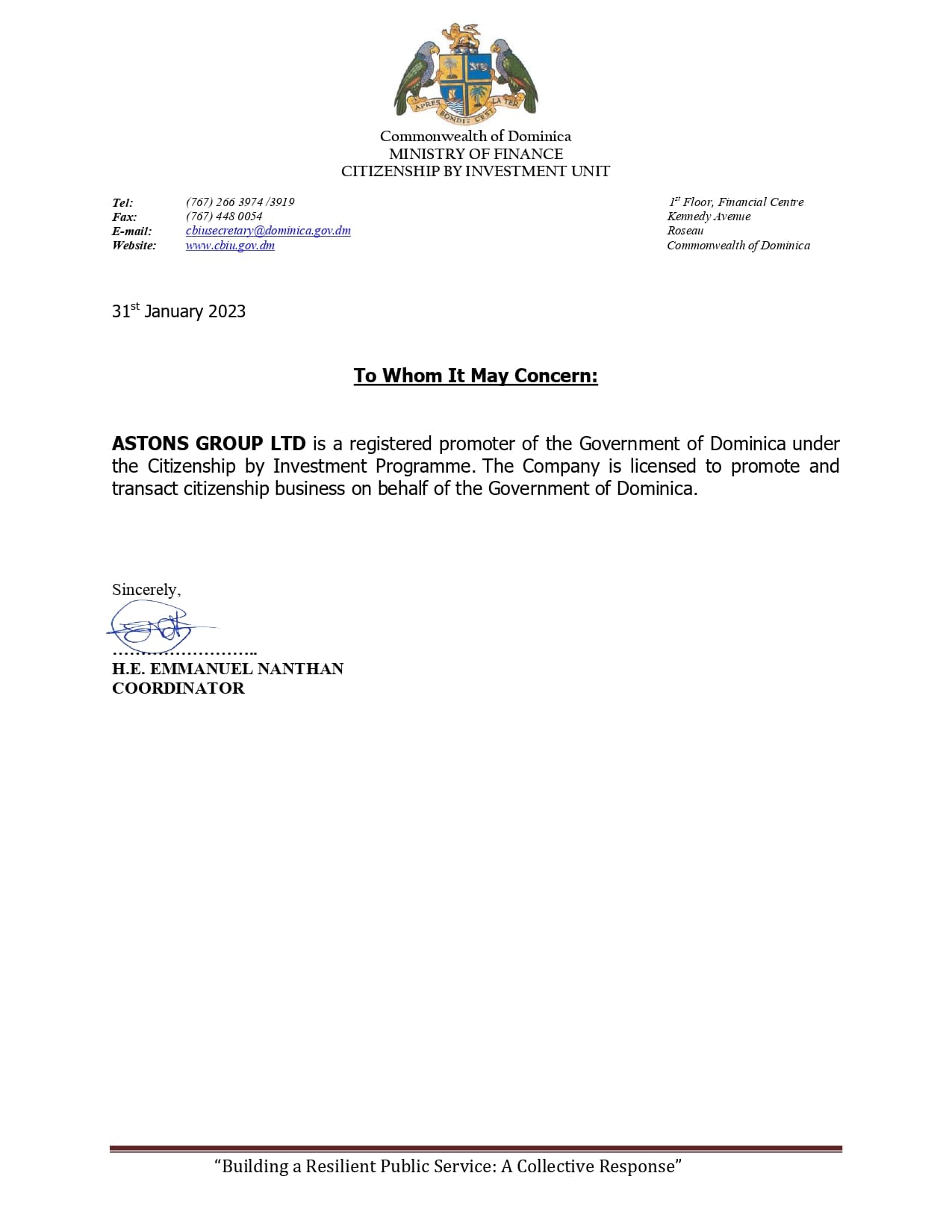

ASTONS maintains licensed partnerships with the official govermental agencies operating the CBI and RBI programs. ASTONS operates in strict accordance with the laws and regulations of every country where we do business - cooperating with local regulators and government officials. Ensuring no risks for you, your reputation or brand, and your investment.

ASTONS, on average, helps nearly 300 clients a year. With historical totals of: More than 9,000 clients A clientele from over 50%+ of the world’s nationalities $2.6 Billion+ USD in immigration and real estate investments

100% of clients who pass the Astons’ due diligence review have their applications approved. The Astons due diligence team of seasoned UK lawyers and industry experts advance our clients’ interests by maintaining direct and constant contact with government officials - leveraging our experience, expertise and methodology of the British law school to conclude the immigration process in our client’s benefit.

ASTONS offers only the best the world of investment immigration and luxury real estate has to offer. We expertly select citizenship and residence programs that can deliver solutions to virtually any client. As well as premium real estate in 11 countries to appease the most discerning buyer or investor. Our experts find the most advantageous solutions to address every client’s wants, needs, and demands.

ASTONS experts are regularly relied upon by global media outlets and publications to provide expert insights and comments for investment immigration; including: Bloomberg, The Times, CNN, The Telegraph, El Tiempo, El Pais, El Economista, MSN UK, SchengenVisainfo and many others.

ASTONS didn’t create the world of immigration investment, we perfected it for the benefit of investors. Astons consistently ranks as a TOP-25 firm in the international immigration industry by Uglobal Immigration Magazine, Best European Citizenship Advisor 2018, and Best Full-Service Investment Immigration Firm 2019.

Astons is a licensed provider of residence permit and citizenship programs

Astons is an officially recognized marketing agent of the Citizenship by Investment program of Saint Kitts and Nevis. The Government of this Caribbean country trusts us to process the documents of future citizens of Saint Kitts and Nevis and transfer their applications for a passport.

Get advice from a leading Astons consultant

At the consultation we:

- Let’s define the investment goals

- We will select an approach to choosing a strategy based on your entry amount and deadlines

- We will choose investment instruments based on the risk strategy and the level of profitability

Contact us in any way that suits you

Susanna Uzakova

Citizenship, residence permit and real estate investment expert

Take the survey and we will select a program for you

Lorem Ipsum

Lorem Ipsum

Lorem Ipsum

Key Benefits of Alternative Residency or Citizenship

High quality of life

The possibility of living, studying, working and doing business abroad.

125+

Countries without visas!

You will be able to freely visit half the world, including the countries of the Schengen area, the UK, the USA and China

5%

Every year, prices for non-movable property in Europe grow on average by.

The future for your children and grandchildren

Tuition on preferential terms in the world’s best international schools and universities. Citizenship is inherited.

Passive income from real estate

Consistently high demand for rental real estate allows you to receive regular passive income.

Rental income abroad is 4-5% per annum, which is higher than the interest on deposits in a foreign bank.

Testimonials

Muhammad, CEO

Qatar

Very impressed by the professional approach of the Astons team. Despite the difficult “covid” time, all issues were resolved very quickly and constructively.

As a result, the process of preparing the entire set of documents for Dominica citizenship for 3 family members took no more than a month, and the passports themselves were received in record time – 3 months after filling out the D1 questionnaire. I recommend this company to everyone.

Luan, Businessman

Aged 65, South Africa

Having reached my 60s, I am less involved with my business and was looking to travel and enjoy life with my partner. It is tough to travel with a South African passport, and obtaining visas is difficult.

I also wanted extra security due to the political situation in my home country. I required a streamlined solution with a reputable investment citizenship program. I reached out to Astons, and Igor recommended Saint Kitts and Nevis Citizenship Program, which has been operating since 1984. The team provided full support with the documents and application, as well as payments, and in three months, my wife and I became owners of the SKN passport. We are now free to travel around the world with no visa implications, and are happy to enjoy our new enhanced lifestyle!

Mahesh, IT Business Owner

India

As an IT company owner based in Delhi, I continuously travel around the world both for business and with my family. I was tired of continuous visa applications and found it impossible to fly during the pandemic.

Having decided that is was high time to secure a second passport we looked around for the fastest and most reliable solution. I contacted Astons and received a detailed quote from Konstantin, based at the London office. I was asked about my requirements and was advised to apply for Vanuatu Citizenship as the quickest and cheapest option. In just two weeks, Astons had completed my application, and two weeks later, my citizenship was approved. I went ahead with my investment, and received my passport two weeks after that, making the whole application process a total of 1.5 months start to finish! Konstantin is an expert, and the team is very professional, so I would highly recommend Astons if you are considering second citizenship and require a fast service.

Lucas, Logistics Business Owner

Aged 45, Brazil

I was interested in a second passport to gain protection from potential risks and attacks on my business by state inspections and other bodies. I also wanted to invest in property overseas to protect my wealth.

After consulting with the Astons experts, I decided to obtain Turkish citizenship via the real estate investment route. Astons’ team prepared a lucrative real estate portfolio for me, showcasing properties in the centre of Istanbul, with 6-7% annual profit yield and the potential to re-sell in 3 years after citizenship had been obtained. The team seamlessly and expertly prepared and submitted the documents, as well as assisting with the property acquisition. After just two months, I received my Turkish passport and would highly recommend Astons to those who are considering second citizenship.

Peter, IT Company Owner

Aged 38

I turned to Astons for a consultation on Caribbean passports, having seen an article about Pavel Durov and how he obtained Saint Kitts and Nevis citizenship. For me, this was relevant since I travel a lot, live in different places, and have long considered myself a citizen of the world.

Therefore, I wanted to get a second passport for global mobility, and to have the freedom of movement any time I travel abroad. I contacted Alexander, who guided me through all the options and explained the advantages and pitfalls to be aware of. My primary intention was to obtain a fast passport for global mobility, so the Vanuatu Program best fitted my requirements. The application process was smooth, and I wasn’t keen to wait for several months for a new passport. What most impressed me was that every timeline Alexander gave me was spot on. Thanks to all of the Astons team for your help, and your excellent work. I could see from day one how hard you all work, with a degree of efficiency, creativity and patience.

Anonymous Anonymous

My experience with Astons has been incredible. After vetting a number of international & Turkish companies for my Turkish citizenship application, I’m so glad I went with Astons. Both Susanna & Alev were outstanding throughout the process & made all the difference.

The entire process was well-defined & thoroughly explained to me, amazing real-estate properties (with great ROI prospects) were carefully vetted for me to choose from, the in-person visit to Turkey was efficient, and the communication from Astons team was excellent throughout. What a great team of experienced professionals to deal with! Thanks for making the entire experience predictable & hassle-free. :pray:

Dana, Holding Group Financial Director

Aged 50, Lebanon

My daughter is 16 years old, and so I needed to plan for her university education. She has a more European mindset, and I have always hoped she would be able to study in the UK, as well as being keen to live in and explore Europe myself.

My career is reasonably successful, so I wanted to diversify my life, travel more often and work remotely. Some friends recommended Astons as having helped them obtain Saint Kitts and Nevis citizenship, so I went ahead, and we discussed various options. The ideal solution was to apply for Cyprus citizenship, being a European Union country and the investment being in reliable real estate. We also had the bonus that my daughter would receive Cypriot citizenship within one year – and therefore be able to choose a university in the UK or Europe. The processing was seamless, and I felt surrounded by great care and attention. Astons’ experts prepared an exclusive property portfolio for me and arranged a virtual tour. They also carried out the essential checks to ensure the safety of my purchase. Now, with a Cyprus passport, I can live wherever I wish, and my daughter can study in the UK. Astons also helped us with her relocation to London and university selection for which I am especially grateful!

Astons в YouTube

Astons at bloggers

Latest articles

Contact us

USA

UK

UAE

Turkey

Cyprus

Greece

Portugal

Malta

- USA

- UK

- UAE

- Turkey

- Cyprus

- Greece

- Portugal

- Malta

Contacts

Show on map

Alena Lesina

Citizenship, residence permit and real estate investment expert in USA

Contacts

Show on map

Yulia Zabyshnaya

Citizenship, residence permit and real estate Senior Advisor

Contacts

Show on map

Igor Nemtsov

Citizenship, residence permit and real estate investment expert

Contacts

Show on map

Contacts

Show on map

Denis Kravchenko

Astons Business Development Director and Head of Astons Cyprus Office

Contacts

Show on map

Contacts

Show on map

Susanna Uzakova

Citizenship, residence permit and real estate investment expert